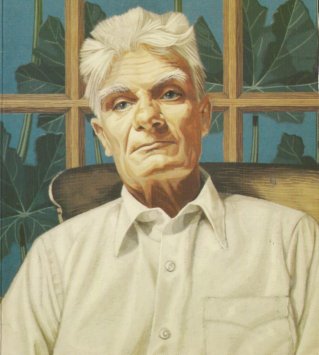

FRANCIS STUART

Francis Stuart was born in 29 April1902- 2 February 2000 and lived in Dublin. He is the author of over twenty novels, including The Pillar of Cloud, Black List: Section H and Redemption, which are autobiographically based. He fought with the Republicans during the Irish Civil War and he spent the Second World War years in Berlin from where he broadcast to Ireland. In 1920 he married Maude Gonne’s daughter Iseult who, like her mother, had turned down a proposal of marriage from Yeats. During the war years he lived with Roisin O’Mara, adopted daughter of General Sir Ian Hamilton, commander-in-chief at the battle of the Dardanelles in the First World War. Hamilton was a German sympathizer and became involved with Hitler in 1936. In 1987, Francis Stuart married Fiona Graham, a thirty-year-old artist. He was awarded the highest artist accolade an Irish Saoi (wise man), a rare distinction in Ireland. Previous recipients of the honour include Samual Beckett, Mary Lavin and Sean O’Faolain. His years in Nazi Germany led to a great deal of controversy.

I interviewed him in 1998 and here is the substance of what he told me then.

You are Australian by birth and Ulster Protestant by background. Did you have the feeling of being different from other people from the beginning?

I did, yes, but probably more because of a certain mystery surrounding my father, who killed himself in Australia when I was only a few weeks old. I never got to know the full circumstances, except that he had made several attempts at suicide and was in a mental clinic in Sydney when he made a final and successful attempt. This haunted and obsessed me, and I began to identify with him very much. His twin brother used to tell me how he had questioned my father, asking him if he felt lonely or persecuted, to which I understand he answered yes. But psychology was not as it is today, and that seemed a very primitive way of questioning. My mother never spoke of him, and nor did her family. I think the marriage was almost certainly unhappy. Although I thought I understood his reasons for suicide, the whole business remained mysterious.

In an article in the Observer last year you were described as an outcast in your own country, ostracized and reviled. Would you agree with that?

No, I wouldn’t mind if it was so, but it is absolutely ridiculous. In certain circles, among cultured people, I am highly regarded. I wouldn’t say I haven’t encountered hostility; as you probably know, I have encountered it everywhere, and here in Ireland not least, but on the other hand it is completely untrue to say I am ostracized and reviled.

You are often described as an incorrigible romantic. Do you wear that description as a badge of honour?

Again, it’s not true. I’m not a romantic, I’m a realist. The imaginative writer must make a model of reality, taking in everything. I have a great admiration for Heidegger who asked: ‘Why is there anything?’ We don’t know a lot, but from what we do know of nature and the cosmos we might expect there to be nothing. I’ve always been astonished at there being anything at all, and I’ve written in poems that it’s a miracle we’re here. Our task, as I see it, is to tend that miracle of existence, experience, consciousness.

Do you think romanticism is dangerous?

As I interpret it, yes, because it’s far from the real. If you make a model of all there is, as the imaginative mind must do, romanticism doesn’t enter into it. Realism, yes. It’s a very harsh planet on which we find ourselves.

In your autobiographical novel Black List: Section H you write: ‘Anyone whose behaviour collides with the popular faith of the time and place is automatically condemned.’ As someone who has experienced widespread condemnation, do you think it has been a price worth paying for your beliefs?

Undoubtedly so for me. I can only do my work after isolation, and it doesn’t matter how I come to be in that condition of isolation. I can’t imagine writing as an accepted member of society, and in so far as I write for anybody, I write for people like myself – isolated, lonely, and very close to despair at times. It’s not necessary for me to have had the life I have had to experience near despair and loneliness; I would have those feelings in any case since they are conditions of living. Without being presumptuous, you very likely have them too. They’re surely common to intelligent, imaginative people.

You were a Sinn Fein sympathizer in the 1920s and 1930s, and you were interned by the British. How did that come about?

I would say Republican rather than Sinn Fein. During the civil war here I was on the Republican and losing side, as I have always been. It is essential in my view to be on the losing side. I was interned for about a year, or perhaps nine months. I don’t remember exactly. I’ve been in six different prisons, mostly abroad, but never for very long. I was never sentenced – there was nothing I could have been charged with – but I was locked up all the same.

Were conditions harsh?

Hunger was the worst. In most prisons we didn’t get enough to eat, but then people on the outside were also hungry. There was overcrowding of course – at one point we had twelve to fifteen men in a cell meant for one or two. That was in Germany where I was interned by the French on the recommendation of the British. I was told that by a French intelligence officer, who said they had to do what the British told them.

What’s your attitude to Sinn Fein today?

If you mean the political party, I dislike all political parties. They give themselves airs and they make not the slightest difference to our lives. Any party could be in power here, it wouldn’t matter which. To my mind they are all a load of rubbish. I’m not the slightest bit interested in politics.

Your first marriage to Maud Gonne’s daughter, Iseult, seems to have all the elements of pain and uncertainty associated with first love and a love that was very young … you were only eighteen. Would you agree with that?

I would, but I should add that the marriage lasted nearly twenty years, although we had terrific rows and so on. I felt very sorry for Iseult. She was one of these innocents, if you know what I mean; she put up with me, which wasn’t easy, and she also put up with her mother, who to my mind was an unpleasant woman. She suffered from both ends.

Was her mother against you?

Yes, but that was understandable. I was an unknown boy from the north, with no background, no money, nothing to recommend me. A boy of eighteen marries her daughter, whom Yeats and other people would gladly have married … I wasn’t a great catch to put it mildly.

The poet Kathleen Raine, whom I interviewed a year or two ago, talks about the purity of young love, which she describes as absolute, the sense that you can’t imagine feeling this for anyone else. Do you remember that first love, the intensity of it, or has it gone completely?

It’s very hard to say with hindsight. What I find is that if I write about certain memories and then try and recall them later, what I remember is what I’ve written about them. If I hadn’t written about them I could perhaps go back to the real thing, but as it is I’m wary of many of my memories. The love we had was certainly one of great intensity, and that meant great rows and violence. We each destroyed things that the other valued. I did some sculpture in those days, and I had one of a bird which I prized very much, and Iseult took that and threw it on the floor. And I once took a pile of her dresses and poured petrol over them.

Do you regret all of that?

In one way I don’t. But I have given hurt, and I do regret that and find it shocking.

In Black List the character H is jealous of the fact that Iseult and the poet Ezra Pound have been lovers … was that something which obsessed you at the time?

I think it did undoubtedly. Sex – sensuality is perhaps a better word – is an extraordinary driving force. And to imagine your partner in the arms of somebody else, that was part of the sensuality. I became obsessed by it.

Did the fact that Iseult had rejected Yeats’ offer of marriage make for awkwardness between you and Yeats later on?

I never found it so. I got on well with him, and he was extraordinarily generous to me. He said that with some luck I would be one of our fine writers. For myself I’m not an admirer of Yeats in one way. He is of course a great poet – it would be ridiculous to say otherwise – but he’s not a poet I would go to for comfort in times of stress. People thought Yeats put on a lot of airs, but he didn’t. He was in fact a very lonely man who would have liked to have had close friends and didn’t. Ordinary people, even intellectuals, couldn’t get on with Yeats much. He had none of the normal social gifts. When we used to stay with Yeats, I’d stay awake all night racking my brains to think of some profound statement to come up with the next day. Sometimes it used to go terribly wrong.

The marriage to Iseult broke up about 1940. So many things were changing and dissolving in those days – did it perhaps seem symptomatic of the times that it should have broken up in 1940?

I suppose it did, yes, and so it was. Many more important things than my marriage broke up at that time.

Can you tell me what it was about Hitler and the Nazi movement which attracted you in the first place?

One of the things which I have always thought so unjust is the powerlessness of the poet. The creative mind shouldn’t be powerless, and the only way the writer is not powerless is if he has a warlord to look up to, as Milton had Cromwell. Only then is he given that power in the world that he believes is his due. I know that to be a false belief now, but at the time I wanted a warlord to revere. If Hitler hadn’t had this manic anti-Semitic obsession, there was a lot to admire in him. But another reason why I went to Germany and later even broadcast from Germany was the business of war itself, which is a terrible thing. If one side wages war because they see another, foreign regime, committing awful crimes, they should know by now that they can’t possibly hope to win that war without using the same, perhaps even more horrible methods, and that was so in the last war. The Allies used similar methods in order to win it, but they went into it saying they were conducting a Christian Crusade, and to my mind that is a terrible thing. It seems to me you are polluting all moral values if you say that. They were defending Europe against a horrible regime, but they weren’t conducting a Christian crusade. By claiming that they were, they were doing something very evil.

Did you ever meet Hitler?

No, but I could easily have done so because the American minister here in Ireland before the war, a man called John Cudahy, asked the Führer if he would grant me an audience. When the war broke out John left the embassy and went to Germany to work as a newspaper correspondent, for the New York Herald Tribune, I think. He had at least two audiences with Hitler, and on one occasion I told him about this neutral Irish writer whose books he had read and liked, and who was in Germany. Hitler apparently said to bring him along, but I never did go. I remember warning John about the dangers and telling him that the British were well aware of his meetings with the Führer and they’d be very happy to get rid of him. He rather scorned the idea, but then he went to Switzerland and within two or three days he was dead. It was reported that he’d had a heart attack or something of that sort, but there was no doubt whatsoever that the British did away with him. Understandably, of course. In war everything is allowable.

Was he very pro-Hitler?

Not so much, but he was advising Hitler not to provoke the Americans into war, and that was the last thing the British wanted.

You have said that you soon discovered that Hitler was not the answer, but one of the reasons you stayed in Germany was because of your hostility to the British. On what exactly was this hostility based?

It was based on their attitude of moral superiority. At one stage the Allied leaders, including Churchill, met in mid-Atlantic on a battleship and sang ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’. That to me was so shocking.

Do you think the hostility might also have had anything to do with the English public-school system which you were part of?

Rugby had a great effect on me – not so much a moral effect, but it toughened me up in a way that allowed me to survive six prisons. None of them was as bad as Rugby.

Do you still have residual feelings of hostility towards the British?

No, not as a people, though I still think their attitude is moralistic.

During the war you broadcast to Ireland from Berlin on behalf of the Reich. What did you feel you were trying to achieve at that time?

It’s not easy now, half a century later, truthfully to recall one’s real impulses, but I thought I might supply the arguments from the other side, since there was nobody to broadcast them to my own country. I never dealt with military matters or the conduct of the war, I never touched on that. I did expose the hypocrisy of the Allied cause, but as it turned out later I never met anyone who ever heard my broadcasts. They went out late at night when nobody was listening.

Setting aside the political aspect, what was life in Berlin like in 1940? Was it a lively place?

Indeed it was, up till 1944. If you had plenty of money, that is.

Did you have plenty of money?

Yes, and I looked to the black market for luxuries. There was plenty of night life too, though I was never one for that.

What about women?

There were lots of women. I had one in particular called Roisin O’Mara, whose origins were obscure to say the least.

I presume she was Irish…

No, I wouldn’t say she claimed to be Irish. She was adopted by an English family, an aristocratic family. Her adopted father was in command at the battle of the Dardanelles, which was a frightful mess-up for the British, as you know. That’s neither here nor there, but it certainly didn’t recommend him as a general. Roisin O’Mara had olive-tinted skin – I would imagine she came from the Middle East.

How did you meet her?

When the war broke out some of my German acquaintances told me that there was an Irish girl studying in Berlin, and she was in a very precarious position as she was undoubtedly a British subject. They asked me to keep an eye on her. I had a very large flat at the time and so I gave her a room. She was actually pregnant and had a baby.

Was that anything to do with you?

No, nothing to do with me. But we became lovers.

What happened to her?

Nothing. She’s still around. She wrote a book in Irish, which unfortunately I can’t read, but I’m told it makes a very strong plea for the other side of the war. There’s a photograph which I took of her in Berlin in the book. She was very beautiful.

You were very fond of her?

Oh, indeed I was. But I never saw her after the war.

Do you find it surprising that fifty years later many people have still not forgiven you for broadcasting from Germany?

Oh no, that is not surprising, that’s very understandable. But I have no regrets.

Your friend Samuel Beckett joined the French resistance and received the Croix de Guerre for his work. Did you never think you might have done the same?

It was entirely convenient for the French to give a high decoration to a foreign collaborator, but I thought it was farcical.

In the afterword to the recent reissue of Redemption, you go some way towards explaining why you spent the war in Germany, ignoring the warning from a professor at Berlin University that by doing so you would be greatly damaging your own future. You explain it in terms of certain events in history having a counterpart, and despite the fact, perhaps because of the fact, that the fight against Nazism was almost universal in the English-speaking world, you thought there was a need, perhaps even a duty, to counter that consensus. Is that a fair way of representing it, do you think?

I don’t think it’s completely fair, because I have always believed that consensus is evil. A consensus of intelligent people is to my mind always wrong. I think it was Simone Weil who said if you see the scales heavily weighed down on the right side, on the moral side, put your small offering on the other side. And I believe she was right.

Do you believe in evil?

Yes I do.

Would you say that a movement, an ideology such as Nazism, could be said to embody evil, and to that extent it is our duty to resist it?

I would answer yes to the first part, that it could be said to embody evil, but that it is our duty to resist it – I wouldn’t necessarily agree with that. You just have to deal with it according to the precise circumstances as they arise in your life. There is no need for a general theory.

Were the Allies right to resist Nazism in your view?

Physically in terms of arms, they were right, but they were not right to claim that they were waging a Christian crusade.

Were you ever afraid that you might actually be hanged alongside people like John Amery and William Joyce who were regarded as British traitors?

It was unlikely because I did not have a British passport. I had one in my youth when I was in the North and we were all part of Britain, but after that I had a valid Irish passport. They could have hanged me, I suppose, but it would have been such a travesty of justice.

Do you think one can be morally neutral?

You can’t have a morally neutral attitude in general but in precise circumstances I think you can. In my situation in Germany it was right to be neutral.

In the afterword to Redemption you also talk of Ireland as having ‘sat out the world conflict on bacon and tea’. That would seem to contain elements of judgement and condemnation…

I was just stating a fact. In Ireland it was called the Emergency, which is a funny way of describing the greatest war in history, and they complained about rationing. They weren’t going to let the business of war interfere with their lives. I’m not condemning them. Why should I condemn them? If I’d been in Ireland I would have also been eating bacon and eggs.

You have sometimes been compared with Jean Genet. Is it a comparison you welcome without qualification?

Yes, I think highly of Genet. He was a fine person. To the world he was amoral, but I think he undoubtedly acted from a certain moral faith, which is rare.

Edmund White, Genet’s biographer, said that again and again Genet was attracted to the person everyone else despised, the lowest person. Do you think that has been the case with you, either in life or in fiction?

It could be, but I think with me that’s incidental. I’m more attracted to the so-called war lords, because they have the power which I think – or used to think – I should have. I believed that imaginative minds, explorers and probers into reality – they should all have power in a just society.

To what do you attribute your success with women?

I wasn’t ugly, let’s say, but also I was positive in my approach to them. I never regarded a woman as just a passing passion or a piece of sensuality. The woman of the moment was always for me THE woman who was going to be with me for the rest of my life. I must honestly say that I think that was to my credit.

Were you sexually driven?

Very much so, yes.

Were you considered a good lover?

It’s very hard to say now. If you’re with a woman in a sensual situation she’s hardly going to say to you that you didn’t live up to her expectations. But I don’t honestly think I was especially good, no.

You seem to have been more than unusually interested in finding the truth, even if it was painful. That is the backdrop to a great deal of your fiction. Do you feel that you have found the truth – if one can put it like that – and was it worth the pain?

I found what I call reality – I prefer the word reality to truth. Truth is somehow a bit pretentious. If you find only a limited reality there is no point in it. You have to ask, what is the greater reality in which this limited reality of daily life is contained?

As a Christian do you believe in an afterlife?

I don’t really believe in heaven. When I say I believe in the Christian faith, I read the Gospels and get a lot of comfort and inspiration out of them. That doesn’t mean I’m bound to take their views as final about anything, but it would be very wrong, just because the Gospels report something which is more or less incredible, to reject them. As regards the afterlife, it’s not a question I’m in a position to answer from the intelligence I have been granted or from the experiences I’ve had. It’s beyond me to say yes or no to an afterlife. There is no point in doing so. In my long lifetime I have some very intense memories of far-back happenings, and I can’t see them being erased completely, even after I die.

Are you afraid of death?

Yes, I would say so, although my fear of death would not take priority over all my other anxieties. If I were to die tomorrow, my greatest anxiety would be what would become of my cat.

Going back to Redemption for a moment, one of the most striking passages reads as follows: ‘There is nothing in the world that couldn’t be called a few scratches, from music to love. It’s a question of making the right scratches.’ Is that a very significant statement for you? Would you say that you have managed to make the right scratches?

It is a significant statement, yes. Whether on a music score or in your own situation, it is only a matter of making scratches, that’s all we can do. As far as my own scratches are concerned, all I can say is that they were always positive. They were always scratches of a believer, rather than a sceptic.

One of the things that struck me when I read Redemption was the business of the girl who was raped. She recounts to Ezra the trauma and says to Ezra that it’s lucky Margaretta is dead because she wouldn’t have to suffer the torment of being raped. And Ezra replies that he would rather Margaretta had been raped twenty times over than be dead. Was that your own view?

Oh yes. Because to be raped would have been nothing to be ashamed of, for her or for me, and to have her alive was everything. I meant exactly that.

Later when Ezra describes a young girl as being raped he said, ‘Violence never takes the shape you imagine it will.’ What has been the impact of violence in your own life?

The impact of violence has been very considerable in my life. I’ve experienced many violent events, and been intimately involved with violence. I’ve heard executions from a prison cell, and I’ve been within earshot of several others.

In the same book Ezra makes a distinction between what he calls ‘a real lover’ and ‘a real and final friend’, saying that a wife is actually a third thing, coming somewhere between the two. He says that ‘to be a wife is to be incapable of the final unjudging friendship’. Is that written more in sorrow than in anger? Has it been a personal disillusionment for you?

Yes, I suppose so. That remark stems from the time when I wanted a ménage à trios with Madeline and Iseult refused. I thought our hearts has been changed by war – my own heart had been changed, and I thought I could bring back Madeline and Iseult would accept it. But their hearts had not changed like mine. And still I thought I could change them. I told a friend, a German professor at the university and he said that was very naïve of me. And then he said a funny thing – he asked me which of them I would go for walks with. I didn’t see it as a problem, but he obviously did.

But presumably there would have been problems. I mean, how would you have organized the sleeping arrangements?

I would like to have acted from impulse. As a writer it’s the only way to act, naturally, as it occurs.

You also write: ‘Marriage may be holy but it is also apt to be heartless as far as the rest of the world is concerned.’ What was in your mind when you wrote that, I wonder? Is marriage heartless?

Oh yes. Couples are heartless, ruthless towards the rest of the world if something from outside threatens them. They don’t have any understanding or compassion…

In your novel Black List you write: ‘Dishonour is what becomes a poet, not titles or acclaim.’ What is the foundation of that belief?

Experience. The creative mind can only write out of isolation which comes from dishonour largely, because if you’re honoured you’re not isolated.

You have – perhaps uniquely, certainly more than most writers – written books which reflect the events of your own life. One might almost say you have lived your own fiction. Do you see it that way yourself? Do reality and fiction ever blur in your own mind?

Yes, they do. It’s partly the fault of my memory, but they do blur, and I believe that that is a fault of many good writers today. The life and work of a writer should not be separate; they should be completely joined.

In Black List you describe how H, after receiving Holy Communion, kneels down by a stone column and says again and again, ‘My Lord and my God’. He then asks whether, if all religion be myth, that invalidates the experience of the moment. How would you yourself answer that question?

No, it doesn’t invalidate it. Even if the Catholic or any other religion is all legend and myth, it doesn’t invalidate it in the slightest. Just as a parable doesn’t invalidate the truth that is represented by the parable. The myth, if it’s intense enough, stands by itself.

Have you thought a great deal about religion during your life?

I’ve thought a lot about it, yes. And still do. I’ve asked the questions, but the answers are quite beyond us.

In Redemption Ezra says to the priest: ‘In general what a horrible egoism family egoism is, and your Catholic family egoism is the nastiest of all.’ Do you believe that?

Yes. I’ve seen it at work. Their absolute ruthlessness against anything from the outside that threatens them is quite shocking, and the Catholic church encourages that attitude.

You have a special affection for Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Why is that?

She was brought up a very strict and pious Catholic, really maudlin – it was quite sickening to read of her early running to the church. And then she got into this convent where she had at least two sisters already, who made it very easy for her. She was a pious little creature, with that conventional piety which is so horrible. After a while, I don’t know how long really, but very soon, all faith, consolation and belief were taken from her. Maybe that’s not the right way to put it, but she lost her faith at any rate. She became as far as possible a sceptic, and I think that must have been a terrible experience. There she was, in the convent, more or less a prisoner. She went there out of belief that she didn’t have any more. And yet of course she didn’t say that she didn’t have it, because she couldn’t have borne it. Then she became tubercular. The Normandy climate didn’t help and she didn’t have enough covering on her cot. Once she woke up in the night coughing, and she could feel her mouth filling with blood. She spat it into a napkin but she didn’t put on the light. In the morning she saw it was obviously arterial blood from the lung and she knew her fate was sealed. The fact that she didn’t put the light on was a great act of self-flagellation.

Didn’t you write about her in a novel?

Yes, it was funny – well, at least the consequences were funny. I was very attracted to Thérèse of Lisieux and I wrote that I was in bed with her that night when she coughed. When she put the napkin to her mouth, I said to her, put on the light, and she said, no I won’t. She only put it on in the morning, and of course when we saw it, we knew she was doomed within a very short period. I wrote all this in a novel and some people who were admirers of my work told me that it was simply horrible of me to write such a thing and vowed that was the last book of mine they would read. They found it offensive that I should have used this obviously very private and painful event in the life of somebody whom I was supposed to revere. I just thought, well, why not.

You have often been to Lourdes. Do you actually believe in miracles?

No. I went to Lourdes because I wanted to wheel the stick down to the grotto, and then into the basilica for the blessing in the evening. I got to know them as I would not have done normally. You enter into other people’s consciousness that way. Of course in many ways it was heart-breaking.

In your novel Memorial, published in 1973, you quote Derek Mahon who speaks in a poem of the author living ‘in obscurity and derision’. Is that how you see yourself perhaps?

Yes, I suppose so. It was certainly the fact of the matter when I wrote it. It’s perhaps changing somewhat now, but it used to be that if my name was mentioned it would arouse quite a bit of derision.

Do you believe you will be read more after your death than during your lifetime?

Yes.

Is that not a bitter thought … or is it one which comforts?

Neither one nor the other really. Historically speaking, I think I won’t be forgotten. But whether that’s a great comfort is another matter. Presumably I won’t be there to get any satisfaction from it.

Would you say you are at peace with yourself now?

No, no. I’ll never be at peace with myself.

Why is that, do you think?

Many reasons, the most obvious being that nobody of imaginative intelligence who finds himself on this very harsh planet can possibly be at peace. Our life is very cruel, and if there is a divine creator, let us say that one side of him is extremely ruthless. He has compassion, undoubtedly, but let us just say that his spirit is very complex.

You were selected recently to become an Irish Saoi, while on a previous occasion you were passed over. Has the establishment now forgiven your sins, do you think, and does it mean fuller recognition of your talent as a writer?

Yes, it does of course. I write in English, which after all is one of the languages that really counts, and as a writer in English I am highly regarded. It would be rather silly of these people in the establishment not to take that into account. They are of course British, and a stupid lot, most of them.

Aren’t you pleased that you’re being honoured?

Not especially, no. I don’t consider it a great honour, but I will go along with it.