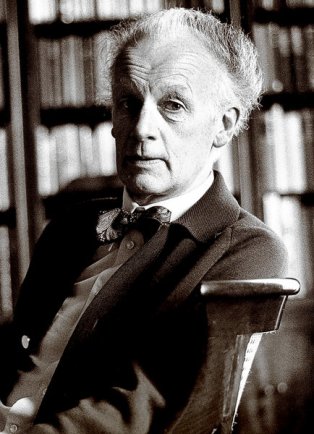

JAMES LEES-MILNE

James Lees-Milne was a conservationist and architectural historian, having written extensively on the baroque, the Tudor renaissance, Indigo Jones and the City of Rome. He was born in 1908 and educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford. From 1933-66 he worked for the National Trust and from 1951-66 he was their advisor on historic buildings. He was also the founding secretary of the National Trust’s country Houses Scheme. He wrote a biography of the 6th Duke of Devonshire, The Bachelor Duke (1991), and his two-volume biography of Harold Nicolson won the Heinemann Award of the Royal Society of Literature in 1982. His four volumes of diaries placed him among the foremost diarists of the century. He died in 1997.

I interviewed him in 1995. Here is what he told me then.

You seem to have a dislike of being labelled – whether it be ‘doyen of conservationists’ or ‘biographer’ or ‘architectural historian’. Would you have any objection to being described as a man of parts?

I imagine a man of parts is someone who is very versatile and good at lots of things. But I’m not good at anything, not even one particular thing.

Your diaries are littered with famous names from the past – Mitford, Pope-Hennessy, Sackville-West, John Betjeman, and so on. Do people nowadays seem very dull by comparison?

Alas, I belong to the past. I wish I could claim to know interesting young people. I do know a few but they can’t be bothered with somebody like me. It’s not that I think young people dull at all but they’re rather different. I’ve got nothing against them, and they are very nice to me and very tolerant, much nicer than my generation were to old people.

You survived an extraordinary childhood, and like most children you seemed to accept your circumstances. Did you sometimes long for normality?

I didn’t think there was anything abnormal about my upbringing, and I don’t think so now. My parents weren’t cruel to me at all; indeed they were very nice to me. My father was rather distant, that’s all, but in those days children were kept in the background. I only saw them at 5 o’clock. I was made to change into a tidy pair of shorts, clean shirt, and then I was pushed by my nurse into the drawing room, where I had to make myself agreeable for half an hour. It was very boring for my parents, and it wasn’t much fun for me.

Although you write entertainingly of your childhood, it seems to have been a rather unhappy time, characterized by fear. You seem to have spent more time with the servants than with your parents – in fact it comes over as a rather loveless environment. Would you agree with that?

No, not wholly, because my mother loved me very much and she was very amusing and unconventional. As I got older and she got older I suppose in a beastly way I became aware of her limitations, and we drifted apart rather. But I always remained very fond of her.

Saying goodbye to your mother when you left for Eton you describe as ‘heartrending’…can you recall that feeling?

Oh yes, but then you see, all boys of my generation wept for days beforehand because school was so horrible. It wasn’t so much that home was so nice, it was because school was so beastly that we wept.

You say that Eton fostered in you intellectual and aristocratic tastes, despite your circumstances which you describe as low brow and lower upper class. Have you felt that as a tension, a dichotomy throughout your life?

My background was a philistine one, that’s to say my father only thought of hunting and shooting and racing and gambling. He wasn’t a rich man, just a sort of ordinary squire, but he lived in a small manor house, so I suppose we were what one calls gentry, but you’ve no idea how limited they were in those days. They despised learning, they never went to art exhibitions, they didn’t go to concerts, their friends were all exactly the same, and I never felt easy with them when I grew up. I did want to get away from them, that’s quite true.

In your autobiography you say, ‘I’m actually conscious of, and amused by, class distinctions. I love them and hope they endure forever.’ What lay behind that remark?

I think class distinctions are fascinating. All the great novels are about class…just think of the Russian classics of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. There’s a sort of leadenness about life when there are no class distinctions.

Does the political idea of a classless society fill you with horror?

It fills me with gloom. It’s not that I like people because they belong to the aristocracy, but on the whole there’s a sort of illumination, a casualness about the aristocratic view of life which I find rather appealing. They don’t take themselves very seriously – think of Nancy Mitford, for whom everything was a joke up to a point – and they’re sophisticated and amusing. Then of course they have lovely country houses to stay in, and the English country house is something very special.

You say you were a terrible disappointment to your father. Was that difficult to deal with?

Yes it was, because he made me feel that I was a total failure because I didn’t have a good seat on a horse. And I didn’t care for shooting. It bored me, and anyway I didn’t like killing things. So he thought I was cissy. He didn’t bother about whether I was doing well in my schoolwork, but he would have liked me to have been sporting and thereby accepted by his friends as a good old chip off the block. As it was, I think they thought very little of me.

After Eton you stayed briefly at the home of Lord Redesdale. How did your family compare with the Mitfords in terms of eccentricity?

My parents weren’t eccentric at all, so there was no comparison to be made. Tom, my friend, was my link with the Mitfords, and it was through him that I went to stay there. I found that Diana, the one who was nearest to me in age after Tom, was mad about poetry and literature, and that was marvellous to me. I realized that there was a world which was completely different from boring Worcestershire, the manor house with its horses and guns, and I thought, this is too wonderful.

Tom Mitford remained your friend until he was killed in the war. You rather gloss over his death in your book…was it shattering to you?

I was very upset, and so were all his friends. We all were devoted to Tom. I saw him the evening before he left England. He didn’t want to fight against the Germans, so he went to Burma and was killed at once by the Japanese. I remember being told of his death by Nancy who rang me up and said in a sort of offhand way, ‘Oh, by the way, you know Tomford’s dead.’ They all had nicknames for each other, and she used to call him Tomford. I thought that was too much of a stiff upper lip, but that was the way they were brought up, not to show their feelings.

You were rebuked by James Pope-Hennessy for what he calls your ‘collapse from pacifism’, which paved the way to your joining the Irish Guards in 1940. Can you tell me how you came to adopt pacifism, and what made you relinquish it?

In between the wars I had convinced myself that the First War was totally unnecessary and was the most appalling calamity, and that no war was ever justified. I don’t think that in the late 1930s I was so aware of the iniquities of Hitler as I was when the war was over, and that applied to a lot of English people. But one of my great friends, Robert Byron, a traveller and writer, was passionately anti-Hitler. I was feeling very ambivalent when the war came, and he convinced me that I should join up and be prepared to fight. So I did.

There were a number of notable pacifists at the time, including Frances and Ralph Partridge. Were you influenced by them at all?

I didn’t know Frances Partridge until after the war. She remains an absolute confirmed pacifist, but the awful thing I learned is that it’s no good being a pacifist unless everyone else is. You’ve got to stand up to evil. And how can you do it except by fighting?

Oxford seems to have been a profound disappointment to you…why was that?

I had the idea that it was going to be a quiet secluded beautiful city, which of course it is, and that there I would lead a cloistered existence, and study, and that dons would take an interest in me, because I was young and earnest. But they didn’t because I wasn’t clever enough, unlike all my Eton friends. They also all seemed to have money and I had none at all. It was very difficult for me, because they used to entertain and give luncheon parties, and there was lots of drink and they were raffish and exciting and thrilling. I couldn’t compete; so I minded.

But did you sow your wild oats in Oxford?

Not very much. I led a quiet life really. I was always very romantic about women and frightened of them when I was young. The idea of casually sleeping with a woman before I was about twenty-five would never have entered my head. Women were people to be courted, and they were romantic. Diana Mitford, for example, was always up there on a celestial cloud, somebody to be worshipped. I suppose I felt sexy, but that was something quite different, and you went to a brothel for that, though I never did. I was terrified of that too. But the idea of meeting a girl at a party and then going to bed with her, it never occurred to me…

Your father had a profound contempt for intellectuals. Did you allow that to influence you at all?

It made me rather secretive in the sense that I would read books under the bedclothes with a torch so that my father wouldn’t see the electric light thorough the crack between the door and the floorboards. And I had to hide my books because when I went back to school my father would throw them away. He thought reading was something rather decadent.

You fell under the spell of Keats, Shelly and Byron, and later Gerard Manley Hopkins. Was Hopkins instrumental in your conversion to Roman Catholicism?

I think he may have been, yes. I thought I was going to write a life of Hopkins. In fact whenever Peter Quennell gave me a book he would say, ‘To the future biographer of Father Gerard.’ Of course I never got down to it; I wasn’t capable of it.

When you were a young man, your faith was uncomplicated, and it took you years to work out that it was because you never associated morals with God. Was it shattering to discover that the two might be related?

Yes, it was rather, because I found going to confession very distasteful. When I no longer belonged to the Church of Rome, I went back to my old church. I’ve always been rather religiously minded. As a child I was mad about God, and still am, and I love talking about Him, but people get embarrassed by God, don’t they? I mean, most of my friends are agnostics, but I’m certainly not. I am a fervent believer, but of course I don’t have to worry about morals now very much, because I have no temptations to steal or go to bed with anybody.

You appear to have lost your faith for a time when, as you put it, ‘morals began to rear their beastly hydra heads’. Was that a difficult time?

It was an embarrassing time. I thought, I can’t go back to the same priest, or any priest, and say, ‘I’ve done it again, father’ – I just can’t. It’s totally off-putting, and I think it’s all nonsense too.

I’m wondering what religion could have meant to you, how it could have been experienced by you as something distinct from moral behaviour…

I think it’s all to do with the afterlife and the purpose of life. I would have found it very difficult to get to the age of eighty-six if I hadn’t believed in God.

In Another Self you describe the period when you were in love with three people at the same time saying: ‘I reached heights of ecstasy wherein I came closer to God than ever before or since.’ That’s quite a significant statement…can you enlarge on it?

It was true. I was in love with two people whom I knew, and one whom I’d never seen, but whom I adored. This was during the war and we simply spoke on the telephone. It is quite easy to be in love with more than one person, very easy indeed. It’s only really embarrassing when they meet.

Sex and God do seem to have been recurrent themes with you. In 1942 you recorded in your diary: ‘The lusts of the flesh, instead of alienating me from God, seem to draw me closer to Him in a perverse way.’ Was that perhaps just wishful thinking?

No, because somehow love or lust did bring me closer to God. I had lustful feelings, but in fact the objects of my desire were nearly always people that I was in love with. I think one can identify the loved one with God, as perhaps nuns and monks do. The sex I had then was not squalid; it seemed to me a fulfilment of myself, almost a sort of union with God. But I think my views of God perhaps are unorthodox. I think of God as the spirit of light and of goodness and understanding…perhaps one shouldn’t really.

After your conversion to Rome you returned to the Church of England. Was your experience of Roman Catholicism a brief flirtation, or was it more like a painful love affair?

I treated it in a rather offhand way. Had I been born a Roman Catholic I should still have been one, I think, but what I liked about being a Roman Catholic was the universality of it, and what always gave me satisfaction was realizing that the mass was being said all the way round the clock – every moment of the day it was being said somewhere, the same liturgy; but when the Vatican Council changed that, I turned against it. I thought it a tragedy.

As a young man you say that the idea of sex without love shocked you. Did it continue to shock you throughout your life?

Oh yes, I was shocked by myself very much when I had sex without love. I thought it was squalid, and of course now that I’m the age I am, sex means nothing to me at all; it’s either a joke or it’s really rather disgusting, besides being a frightful bore.

There is a very poignant account of a brief but intense friendship with a young man – Theodore, I think – which ends in tears. It also seemed to strain the limit of heterosexuality…was that a worry for you?

No, not a bit, because I’ve never discriminated between hetro- and homosexuality really. I think you can be in love with both, you know…I’ve always found that.

Your first employment was a private secretary to Lord Lloyd from 1931 to 1935. Did that suit you or did you have the feeling that you were in the wrong job?

I felt that I was not in the right job, that I had my way to make in the world, that it was only an interim job, and he realized that too. But looking back on it, it was a very good experience for me because he was a task master and I learned how to work hard.

You then held the post of adviser to the National Trust, which seemed tailor-made for you. In terms of satisfaction and job fulfilment, how would you compare that part of your life with your literary activities?

Although I had secret literary ambitions I never thought I was going to write books until the war. So during the 1930s there was no conflict at all. I dedicated myself to the National Trust work and didn’t even think of writing books.

Do you see yourself as having being engaged in a war with the philistines, preserving wonderful buildings from acts of vandalism, and so on…?

Oh yes, very much so. I was one of the founder members of the Georgian Group in the 1930s, and it was a fight to get the public to recognize that classical buildings in this country were of any importance at all. The Ministry of Works, the government department which had care of the ancient monuments, said that architecture in England ceased in 1714, the year that Queen Anne died, and therefore no Georgian building was even worth looking at.

You are a distinguished biographer, most notably of Harold Nicolson and the 6th Duke of Devonshire. On the face of it biography would seem to be an art form distinct from novel writing or autobiography, but do you perhaps think that the distinction is sometimes blurred, that biography is often closer to fiction than we imagine?

I think you have to control yourself. You mustn’t fictionalize or allow your imagination to take flight when you’re dealing with another man’s life. You have to be careful not to let your prejudices run away with you, and you probably can’t write a very good biography if you dislike your subject.

You have sometimes said that your prefer writing about rogues. What is it that attracts you to rogues?

It is easier to write about rogues than about virtuous men. To write the life of a saint would be frightfully difficult unless it was a funny saint. One of the reasons why newspapers are so wicked and have such an appalling effect on people’s lives is because they deal with bad news and bad people. Good people’s doings are very boring.

Your novel Heretics in Love deals with the themes of Roman Catholicism and incest. Was it meant primarily as an entertainment, or were you intending it as a serious expose of moral and religious problems?

I was trying to see whether one could make a tale of that sort seem plausible. It is about twins of the opposite sex who had grown up in the country as Catholics and had not known or consorted much with the outside world. I wanted to test whether it was possible for two people brought up in those circumstances to fall in love; and whether it was pardonable.

In your third novel, The Fool of Love, the squire Joshua says, ‘So long as one is madly in love one is living in a fool’s paradise.’ Was that remark based on your own experience perhaps?

Yes. Because I think when people are passionately in love they are mad and very unreliable. I think that if one knew that the prime minister was carrying on a passionate affair with someone, one would feel extremely nervous in a crisis.

You were in your forties when you married…were there times before that when you contemplated marriage?

The people I would like to have married were either already married or turned me down, so then I didn’t bother very much for a while. And then suddenly I met Alvilde and I fell in love with her. That was difficult because I was still a Catholic and she had been married before and had a child. She had had a very unsatisfactory married life, in fact she often used to say she couldn’t think how her daughter was ever born at all. Her husband was in love with somebody else, so she had a rotten life. We tried very hard to get an annulment for her, but it turned out to be quite impossible. If it had happened today we probably wouldn’t have cared tuppence whether we were married, but it did seem to matter then, and we were very conventional.

You never had children of your own, and relations with your stepdaughter seem to have been strained. Did you, or do you dislike children?

I don’t care for children very much. When they’re responsive and affectionate I think they’re sweet and nice, but on the whole I find them awfully boring until they’ve become adults.

One review wrote of your latest volume of diaries: ‘Some of Lees-Milne’s opinions are now so wildly outdated and unfashionable that one has to remind oneself that these diaries were written before anyone had thought of political correctness.’ Do you have a view on political correctness?

I think it is deceitful. I’m often accused of being a snob, but really I’m not. What I am is an unashamed elitist; it’s not reprehensible to want to know people who are cleverer than oneself or more amusing.

After hearing a communist express the view that the needs of poor people should take precedence over those of the upper class, you decided that left-wingers were evil and wrote in your diary, ‘I have no sympathy for them at all. Let them burn.’ Is that not an indefensible remark, then as now?

Oh the left-wingers, well, I don’t fancy them. I’m very impatient with them.

Is it difficult not to regard some passages in your diaries as impossibly right wing and racist. For example, a television programmes about Bangladeshis led you to write: ‘Such people ought not to exist…these ghastly people are a sort of standing or seething pollution of the western world’s perimeter, of the civilization we have known. I can’t stand the Orientals, their deceit and abominable cruelty.’ Would you still stand by such comments today?

Very often I would. There are altogether too many of us, and the danger in what is called the third world is absolutely terrifying. Until they can be stopped breeding I really do think the future is very bleak indeed. But I agree, it is a very offensive remark.

In your autobiography you wrote, ‘I prefer to be in the running without ever winning than never to run at all.’ Is this modesty, or lack of ambition?

I don’t think I am ambitious but I do like successful and interesting people, and I’m grateful that they’ve wanted to see me because I get more out of their company than they do from me probably. My life has not been full of achievements. I have yet to write a book that I think is much good. I’m not at all satisfied with myself.

The researcxhers warned automotice companies that the extra related cars grow

to be, the extra likely they arre to geet hacked. http://mostpopularlike.com/Other/dodge-durango/

LikeLike

1- Anágena ou fase de crescimento dos cabelos. http://dev.itidjournal.org/index.php/itid/user/viewPublicProfile/14184

LikeLike